The next time someone says to you, “Gee, you look great for your age,” do this: look at them suspiciously out of the corner of one eye and in a low, conspiratorial tone, mutter, “ what exactly do you mean by that?”

Your friend will be taken aback (or run away) and not likely to ever offer up a compliment again but you would be in the right.

Huh?

According to the Washington Post, new research work from Stanford University has come up with startling – or utterly obvious – conclusions about how we age. More specifically, what parts of us age at what speeds.

Startling, because they discovered that lab mice, those little guys who are genetically engineered to be clones of each other, actually age at different rates and in different organs in their supposedly identical little bodies while being raised in perfectly controlled and identical environments.

Intellectually interesting, perhaps, but as an old Journalism prof of mine at university liked to ask his students struggling to find the focus of a story, “how does this affect my sex life?”

In other words, so freaking what?

Well, the boffins at Stanford found it intriguing enough that one mouse’s liver seemed a lot “older” than his identical twin sister’s that they decided to see if the same thing occurred in humans.

Lo and behold, they found that human organs aged at different rates in different people. In fact, a human heart for example, could age faster or slower than a human liver in the same body.

Now, the conclusions they came to could have been scripted by Captain Obvious, himself.

One of their conclusions is…wait for it…if you have a heart that ages faster than any other organ in your body, you are more susceptible to heart disease, heart attack or death than someone who is the same chronological age as you but whose heart is “younger.”

The discovery applies to pretty much every other human organ as well. In effect, these scientists have determined that there is chronological aging and there is biological aging.

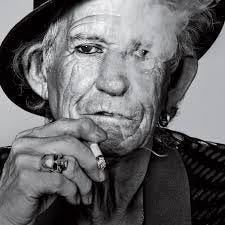

The best living example of this conclusion is the man in the picture below:

Keith Richards, God bless him, is 81. His lungs were probably 81 when he was 22. And his liver…well…

The other primary conclusion from the extensive Stanford study, which tapped into a massive blood and health record database in Great Britain, and used AI to sort for results, was, again, no big surprise. If your heart is aging faster than the rest of you, look to diet and exercise to turn things around. There’s just no ducking self-discipline, I guess.

A two-time guest on The Art 2 Aging’s podcast, cardiologist Warrick Bishop, would strongly suggest imaging the heart muscle as well because there’s a reason why your ticker’s tock is off.

Think about it: your heart isn’t aging faster by coincidence. There has to be a definitive reason. This rationale applies, of course, to any organ which seems to be “out of time” with your other organs.

As far as the human brain is concerned, again, the researchers found that an “old” brain was more than three times likely to fall victim to Alzheimer’s Disease than a “younger” brain.

As full of data-backed research and important sounding conclusions as the study was, the big question remains unanswered, even if never asked: WHY?

Why does one organ age faster than another in the same body? If one’s body is subject to its environment on a minute-by-minute basis, why are one’s kidneys aging faster than one’s spleen, stomach, or gastrointestinal tract?

Doesn’t epigenetics impact the entire body in the same way, at the same time?

Apparently not. So there must be another reason. But the researchers aren’t able to answer that question.

Could it be that the answer isn’t based in the physical, but in the infinitely larger non-physical, what quantum scientists might refer to as the Information Field?

Deepak Chopra puts it succinctly: “how does the body synchronize long-range time (including the loss of baby teeth for mature teeth, the onset of puberty, and the arrival of menstruation), mid-range time (including the cycles of digestion, hormones, and sleep), and short-range time (including thousands of nearly instantaneous chemical processes at the cellular level)?”

How, indeed.

And of course, we are not issued the same set of organs during manufacturing… we don’t live the same type of life, respond to stress uniformly, and our behaviors vary greatly. Robert Sapolsky wonderful ‘Behave’ will be a good read in this context.